What is Good Now?

Listen to the Editorial Conversation for this chapter:

“Modernity is a deal: … humans agree to give up meaning in exchange for power” [1]

The contemporary modernity[2] we are born into has seen the destruction of shared meaning. We, civilized humans of the modern world, are no longer born into a social construct that moralizes our actions or beliefs in terms of divine will; we no longer derive our place in the world from our clan, tribe, nation, or creed – we are an individual. We have reached the point in the human story where we have destroyed most shared sense of meaning and traded meaning for power. Our collective, human, power now controls the fate of the world – the construction of dams, the irrigation of cities in the desert, and the ability to move goods from anywhere in the world to an apartment in Manhattan[3].

This power we find ourselves with is both topical and mundane. You may eat eggplants grown across the country with Miso made in Japan and premium salt from Australia – it took no extra effort to source these items and in fact, it may have taken less effort, as you bought what others already thought was good. The power is both collective and individual; wielded by human organizations, rewarded by market forces, and consumed by you.

Our tastes, accents, mannerisms, and values are products of our social environment, including our culture and an individual’s access to capital. We don’t just pick the culture we like; we are born into a culture and a class from which we inherit a view of the world[4]. Culture makes us more or less likely to act in certain ways, prefer certain things, and seek out different types of experiences[5].

The destruction of shared meaning has led each stratified band of social class to re-construct its own codified sets of personal meaning. These biases, virtues, and preferences are available wholesale – and sold to you by the merchants and practitioners that support these groups[6]. These mass market constructs are available cheaply or free of charge; they may be right or wrong, and they may rightly make you either a happier or more thoughtful individual – but they are not exclusive. The distinction between high-capital groups and pop culture shifts over time, as each adopts aspects of the other, as the high culture is commoditized and the low culture is elevated[7]. Our preferences in art, literature, and music are partially determined by our social position – our family’s exposure to specific cultural artifacts, the economic possibilities we inherit, and the interest of the teachers whose classes we pass through.

High capital groups have historically kept their ideals and preferences from the public eye. The unwritten rules of high-capital society are themselves constructed such as to be a gate keeper for those who had no ability or opportunity to learn the expected behaviors, attitudes, and language. One either knows the unwritten rules needed to act the part and be accepted in high-capital society, or not. The tastes of some social groups are valued more highly than others because they confer status: reading Homer verses Harry Potter; enjoying classical music verses pop music.

Yet, we must ask: why, in both low and high capital society, are tastes so uniform and predictable?

The enforced conformity amongst peer-groups, who share in their social-capital, is a driver of the cultural differences between the strata of social-classes. Those with less social or economic capital are not restricted to learning the culture and values of those with more capital – every socioeconomic class creates its own norms and values; often the group norms for conformity and exclusion are more rigorously enforced in the lower classes verses the increasingly globalized and culturally omnivorous laissez-faire culture that has become the norm in upper classes[8]. Individuals learn and conform to the highest-status contortions of behavior, vernacular, and preferences from which they experience and which conforms to their classes’ expectations. Knowledge of the unwritten rules is itself cultural capital, conferring status on those “in-the-know” – the lack of cultural capital is used to exclude those who fail to use the right language and exhibit the behavior expected of high-status individuals. Each strata polices the actions of itself, with threats of ridicule, exclusion, or even violence for those who don’t adopt the norms of the group. There is a large weight of social pressure, from institutions such as schools and media, to the relational such as parents and friends.

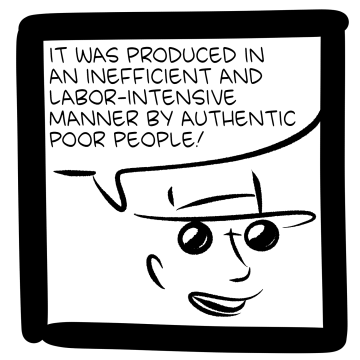

Of most interest to practitioners of Chinese Tea Ceremony[9] is the western-contemporary high-capital ideal of cultural omnivorousness: High status is now expressed by knowing about many cultures, and their authentic pre-industrial products, not just any one culture, high or low. The status seeking activity in the contemporary practice of Chinese tea ceremony is the search for authenticity. As the world has become increasingly globalized and homogenized within high-capital society, practitioners of many praxes have begun to search for meaning through the authenticity of pre-industrialized or pre-globalized products – including tea. In the west, we look for the “traditional” teas, and try to practice the most “traditional” form of Chinese Tea Ceremony – these are status seeking desires to link our own practice to the social capital generating ideal of authenticity.

“… when we take a closer look at many supposedly ‘authentic’ activities, such as loft-living, ecotourism, or the slow-food movement, we find a disguised form of status-seeking.” – Andrew Potter, professor of Philosophy, McGill Institute

Authenticity comes in four forms[10]:

Type Authenticity: Authenticity from conformity to a set of expectations for the claimed category (Bern’s as a steak house, Katz as a delicatessen, Atlas as a gin bar, and A La Biche Au Bois as a French Bistro).

Moral Authenticity: Authenticity from an object or ritual imbued with moral meaning (items: organic, grass-fed, cage free, all natural, and small farm; ritual: traditional, revivalist, and esoteric).

Craft Authenticity: Authenticity from application of advanced knowledge, skills, routines, tools, and ingredients (brewing small batch beer, growing grapes for wine, cooking poisonous fugu, and house made vinegars and pickled vegetables).

Idiosyncratic Authenticity: Authenticity from symbolic or expressive interpretations of an entity’s Idiosyncrasies (authentic for being unique; authentic for being first if others copy).

What attributes give food authenticity?

The General Case

- Creation by hand versus industrial process (craft authenticity)

- local settings and anti-commercial ideals (moral or craft authenticity)

- sincere expression, no calculation or strategy (type authenticity or idiosyncratic authenticity)

- Closeness to nature (moral authenticity)

Wine[11]

- Historicity: stories of the founder and a history linked to known events (type authenticity)

- Terroir: the unique flavor of a place (moral or craft authenticity)

- Traditional, difficult, labor intensive, or low success rate methods of production (craft authenticity)

- Focus on ingredients (craft authenticity)

- Downplaying of commercial motivations (craft authenticity)

As shown in the above example, food in general can take on any of these types of authenticity, while some praxes attract practitioners focused on a specific aspect of authenticity (for example, wine predominantly uses craft authenticity, with some “natural wine”[12] now using moral authenticity). The communication around natural wine, and a certain contemporary generation of food products generally, has increasingly relied on the language of negation: no added yeast, no filtration, no sulfur, no new oak, and no additives (such as oak flavor or enological tannins). The language of “no” serves as a virtuous signal to the wine’s “naturalness” and a distinction from other “not-natural” wine.

The high demand for authenticity has led to its use as an iconoclastic shield for products that could not sell on their own merits – a flawed wine called out as such, promoting its “funky indigenous yeast” or a tea harvested on a rainy day, dried by a fire with its remnant smoky flavor, described as “traditionally produced in a wood fire heated hut”. Marketing a products’ flaws is not new; marketing has always attempted to align what consumers value with each products’ attributes. Natural wine and high-end tea today are sold through stories: “4th generation estate wine aged in restored clay amphora”, or “4th generation tea master made traditional pine-wood smoked TongMuGuan (桐木关) Village ZhengShan Xiao Zhong (正山小种)”; these products may be good or bad, yet the value rests in the story – at least before the product is tasted.

The search for authenticity within the contemporary high-capital ideal of cultural omnivorousness, when paired with globalization and its distribution of tradition and its homogenization of global cultures, frequently ventures into exoticism – the projection of high-culture fantasies about profound cultural differences onto lower economic-capital and lower-class groups. Exoticism allows high-capital tea buyers in the west to fantasize about the idyllic life of tea farmers lightly tromping through high mountain paths in Xishuangbanna, preserving their family’s tradition of making tea by hand in a rural village without electricity. Exoticism conveniently ignores the low wages, low educational opportunities, lack of modern conveniences, and the back-breaking labor traditional methods frequently rely on.

Foods are frequently framed as exotic in contemporary marketing, associated with poor, rural people in developing countries, even when the target is a common product from the western world:

“pasta made by women who measure weeks in flour and seasons in egg yolks and every fold and crevice of noodle can seem as eloquent as a sigh” (Gourmet, January 2004, p. 46).

“food that is produced and consumed in “a medieval Italian town” that “rises from oblivion in the mountains of Abruzzo”’ (Gourmet, September 2004, p. 139).

Exoticism isn’t new. Art and literature are rife with high-capital societies casting their gaze on the noble savages of low-capital societies, and projecting their desires for a simpler, happier, life onto the scene; or imagining the abundance of high-status goods in their place of origin, with fantasies of opulence and “barbaric splendor”[13].

Saada, the Wife of Abraham Ben-Chimol, and Préciada, One of Their Daughters, 1832

Why Are You Angry? (No Te Aha Oe Riri), 1896

How is tea any different? It is not. Our contemporary high-status culture has adopted authenticity to construct meaning in a meaningless world. What makes tea authentic?

- Historicity: the family has been farming tea for 200 years

- Terroir: the family has been harvesting wild tea in YiWu (易武) for 200 years

- Traditional methods: the family roast tea over hardwood charcoal

- Craft ingredients: high-mountain tea from ancient arbor trees

- Purity of Motivation: I remained a poor organic tea farmer because I love tea and want to preserve my family’s heritage and history

All of the components of Type, Moral, Craft, and Idiosyncratic authenticity appear in the desire for some teas over other teas. The marketing of teas, the explanation we give to friends and students, and our own preferences, are all couched in terms of authenticity[15].

How much of our desires are our own? We are individuals and we are products of our culture; our preferences are personal and our preferences are shared; we are rational and we are involuntarily programed by society – the tension of our reality pulls on each of us, reversing the causality of our experience. Bourdieu asks “who prefers it?”. I ask who are we to know what is good now?

The Chinese Garden, 1742

[1]Harari, Yuval Noah. 2016. Homo Deus. London, England: Harvill Secker, pg 200

[2]Modernity may be understood as the systemization of culture, society, and self; the view that the system can be understood, and optimized, and changed.

[3]From where I comfortably write this book.

[4]And that view, throughout the word, is now liberal individualism. Liberal in the philosophical sense, not the narrow United States political sense.

[5]That is why, for instance, a 16-year-old American girl in high school today is unlikely to enjoy 16th century Mongolian folk songs.

[6]For example, an array of churches would be happy to have you join and follow their rules. Or, for a more contemporary example, the lifestyle influencers on Instagram or TikTok can tell you their philosophy for self-realization for a “follow”.

[7]Such as the adoption of African American based vernacular and music amongst high-capital US culture.

[8]Imagine for a moment the difference in response between a high-capital and a low-capital group to the same situation: a young middle school aged male begins ballet training. To the high-capital group, this may be just another set of lessons next to viola and French classes. To the low capital group, this may be a threat to the sanctity of manhood – and likely leads to ridicule, exclusion, or violence as a form of social repression for behavior and preferences outside the in-group norm.

[9]Of whom advanced practitioners tend to be moderately wealthier and better educated then the general population.

[10]Heavily cited from: Carroll, Glenn R., and Dennis Ray Wheaton. "The organizational construction of authenticity: An examination of contemporary food and dining in the US." Research in Organizational Behavior 29 (2009): 255-282

[11]Beverland M. The ‘real thing’: Branding authenticity in the luxury wine trade. Journal of Business Research. 2006 Feb 28;59(2):251-8

[12]Low or no sulfur wine made with naturally present yeast (instead of commercial yeast used for a controlled fermentation) and no flavor or fining additions; alternately called no-intervention wine. Discussed in some detail in the previous section: The Future of Tea Ceremony: Bottom Up.

[13]Sir Richard F. Burton (1821–1890).

[14]“At the atelier of the Tropics, I will perhaps become the Saint John the Baptist of the painting of the future, invigorated there by a more natural, more primitive, and above all, less spoiled life” - Paul Gauguin letter to Vincent van Gogh (1890).

[15]Jin Jun Mei (金骏眉) may be the triple platinum pop-album of tea; a new development in a new style, it was popular, expensive, and everywhere for a time. Jin Jun Mei was a clash of high and low culture, promoted by taste makers, praised by critiques, yet fleeting in its popularity. Why was it only good for a few seasons? Why did its popularity fade? What can we make of the short history of Jin Jun Mei?

[16]While I hope to soon find a Chinese garden of my own to relax and brew tea in, I can’t escape the vision of earlier Europeans engaging in orientalism, playing dress up and drinking their “exotic” tea. Has our culture and desires progressed since this was painted?